Sprawling across more than 200 acres near modern-day Luxor, the Karnak Temple Complex stands as one of humanity’s most impressive architectural achievements. This vast religious compound, developed over more than 1,500 years by successive generations of pharaohs, represents the largest ancient religious site ever built and offers an unparalleled window into the grandeur, spirituality, and engineering prowess of ancient Egyptian civilization.

Construction at Karnak began during Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (around 2000 BCE) under the reign of Senusret I, but the most significant expansion occurred during the New Kingdom period (1550-1070 BCE) when Egypt reached the height of its power. For over 35 generations, pharaohs added their mark to this sacred precinct, each contribution reflecting shifts in religious practices, political power, and artistic styles.

Unlike most ancient monuments that represent a single moment in time, Karnak evolved continuously, with each ruler attempting to outdo his predecessors. This multigenerational project created a living historical document in stone—a physical timeline of ancient Egyptian history, religion, and architecture spanning from Middle Kingdom simplicity to New Kingdom grandeur and beyond.

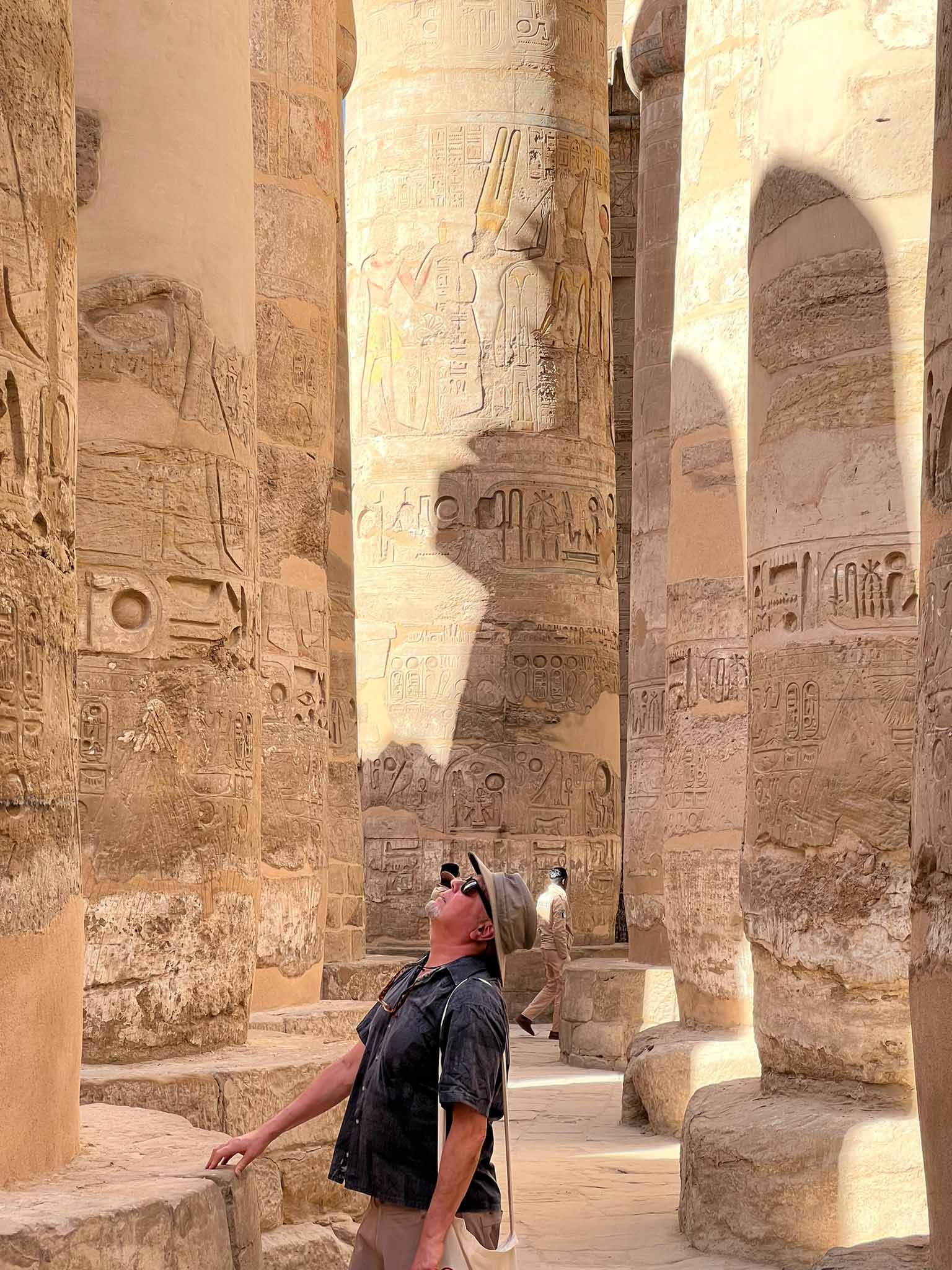

Perhaps Karnak’s most awe-inspiring feature is the Great Hypostyle Hall, constructed primarily during the reigns of Seti I and Ramesses II (13th century BCE). Covering an area large enough to fit both Notre Dame Cathedral and St. Peter’s Basilica, this colossal hall contains 134 massive columns arranged in 16 rows. The central 12 columns stand a towering 69 feet high, with capitals large enough to accommodate 100 standing people atop each one.

Early visitors described walking through this hall as moving through a stone forest. Even today, travelers are humbled by the sheer scale and engineering precision. The columns, deeply carved with intricate hieroglyphics and religious scenes, originally supported massive stone roof blocks—a feat requiring mathematical and architectural knowledge that continues to impress modern engineers.

The walls and columns preserve remnants of the brilliant colors that once adorned the entire temple. These vibrant pigments—blues, reds, yellows, and greens—would have transformed the stone forest into a kaleidoscopic experience, their symbolic meanings as important as the carved images they enhanced.

Karnak was primarily dedicated to the god Amun-Ra, who rose from local Theban deity to national god as Thebes (modern Luxor) became Egypt’s capital. The complex comprises three main temple enclosures: the Precinct of Amun-Ra, the Precinct of Mut (Amun’s consort), and the Precinct of Montu (a war god). Additional smaller temples and shrines dot the landscape, creating a truly divine cityscape.

A nearly two-mile avenue of ram-headed sphinx statues once connected Karnak to the Luxor Temple, creating a ceremonial processional route for religious festivals. During the annual Opet Festival, statues of Amun, Mut, and their son Khonsu were carried along this avenue, accompanied by priests, musicians, and the pharaoh himself, celebrating the renewal of royal power through divine connection.

The temple layout follows traditional Egyptian sacred architecture principles, with increasingly restricted access as one moves deeper into the complex. While outer courtyards welcomed common Egyptians during festivals, inner sanctuaries were reserved exclusively for high priests and the pharaoh. At the heart of Amun’s precinct lies the Holy of Holies, where only the high priest and pharaoh could enter to commune directly with the god’s spirit, believed to inhabit a sacred statue.

Beyond its religious significance, Karnak demonstrates the Egyptians’ remarkable engineering abilities. The massive obelisks—single pieces of granite weighing hundreds of tons—were quarried in Aswan, transported over 100 miles via the Nile, and erected with perfect precision. The largest standing obelisk at Karnak rises 97 feet and weighs approximately 323 tons.

The complex also reveals ancient Egyptians’ sophisticated understanding of astronomy. Key structures align with seasonal astronomical events, particularly the summer solstice, when the sun’s first rays penetrate to the sanctuary’s deepest chamber. This alignment connected earthly religious practices with cosmic cycles, reinforcing the pharaoh’s role as mediator between heavenly and earthly realms.

Karnak’s walls serve as monumental historical documents, covered with hieroglyphic inscriptions recording religious texts, royal decrees, and battle accounts. The famous Battle of Kadesh between Ramesses II and the Hittites appears in detailed relief carvings. The “Bubastite Portal” preserves the first historical reference to Israel in Egyptian records. Political propaganda intermingles with genuine historical documentation, challenging modern historians to separate fact from royal self-glorification.

The temple also houses the famous Karnak King List, where Thutmose III recorded the names of royal predecessors he considered legitimate—while conspicuously omitting those he wished history to forget, including his stepmother Hatshepsut. Such selective historical editing reminds us that even monumental stone records reflect political viewpoints rather than objective history.

Karnak’s importance diminished as Egypt’s political center shifted northward in the Late Period. The temple continued functioning into the Ptolemaic and Roman periods but gradually lost prominence. By the medieval period, parts of the abandoned complex were buried under sand and silt from Nile floods, while local villages incorporated other sections into newer buildings.

European travelers began documenting Karnak in the 17th and 18th centuries, with systematic archaeological work beginning in the 19th century and continuing to the present day. Modern conservation efforts face the dual challenges of preserving these ancient structures while making them accessible to the millions of tourists who visit annually.

Today, Karnak stands not only as Egypt’s most visited ancient site after the Pyramids of Giza but as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and an irreplaceable record of one of humanity’s greatest civilizations. The temple complex continues to yield new discoveries as archaeologists utilize advanced technologies to uncover buried structures and decipher faded inscriptions.

For visitors standing in the shadow of Karnak’s towering columns, the overwhelming sense of human ambition and religious devotion transcends the millennia. These massive stones, raised toward the heavens by ancient hands, continue to fulfill their original purpose—connecting humanity with something greater than ourselves and preserving the memory of those who came before us.