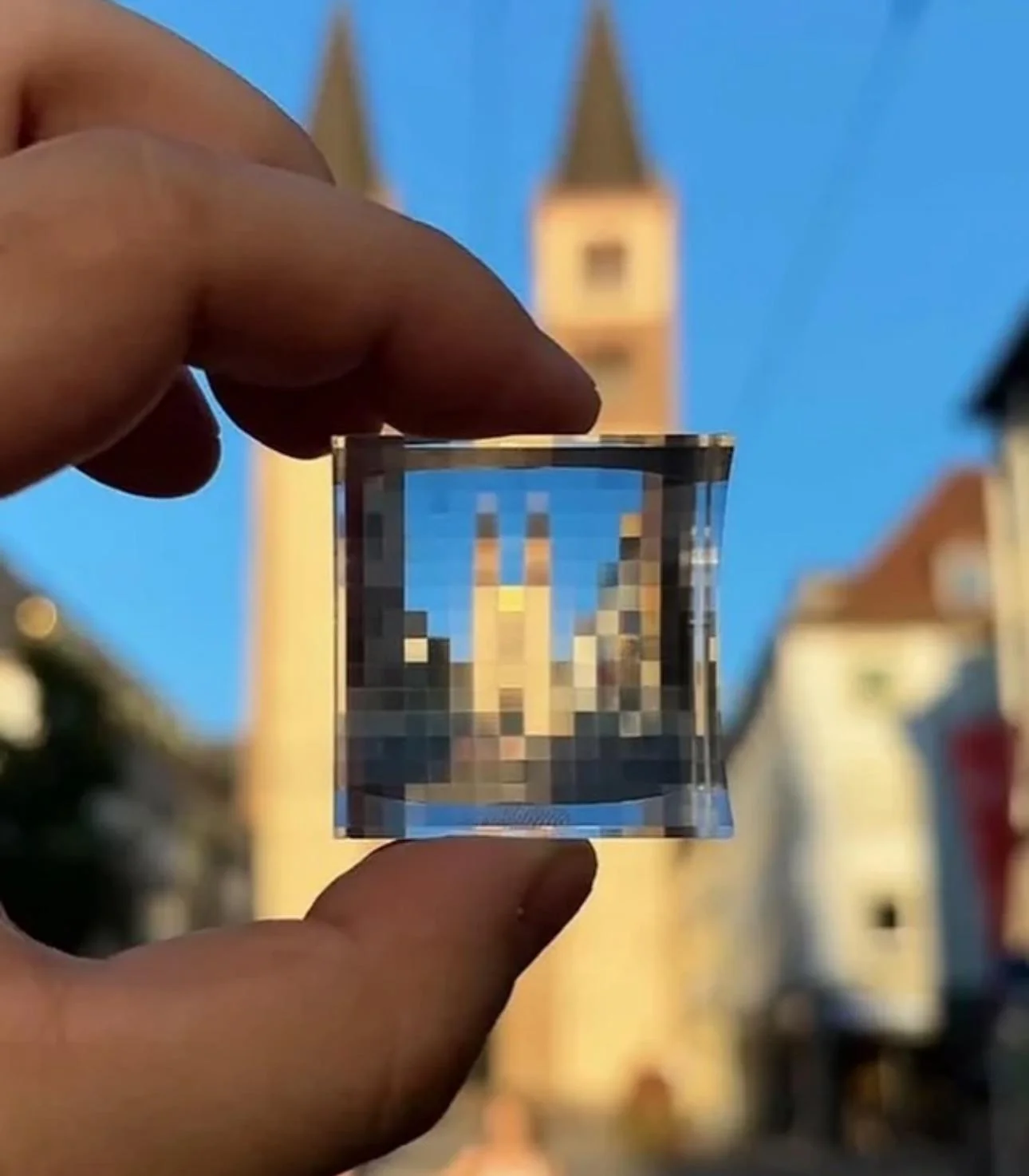

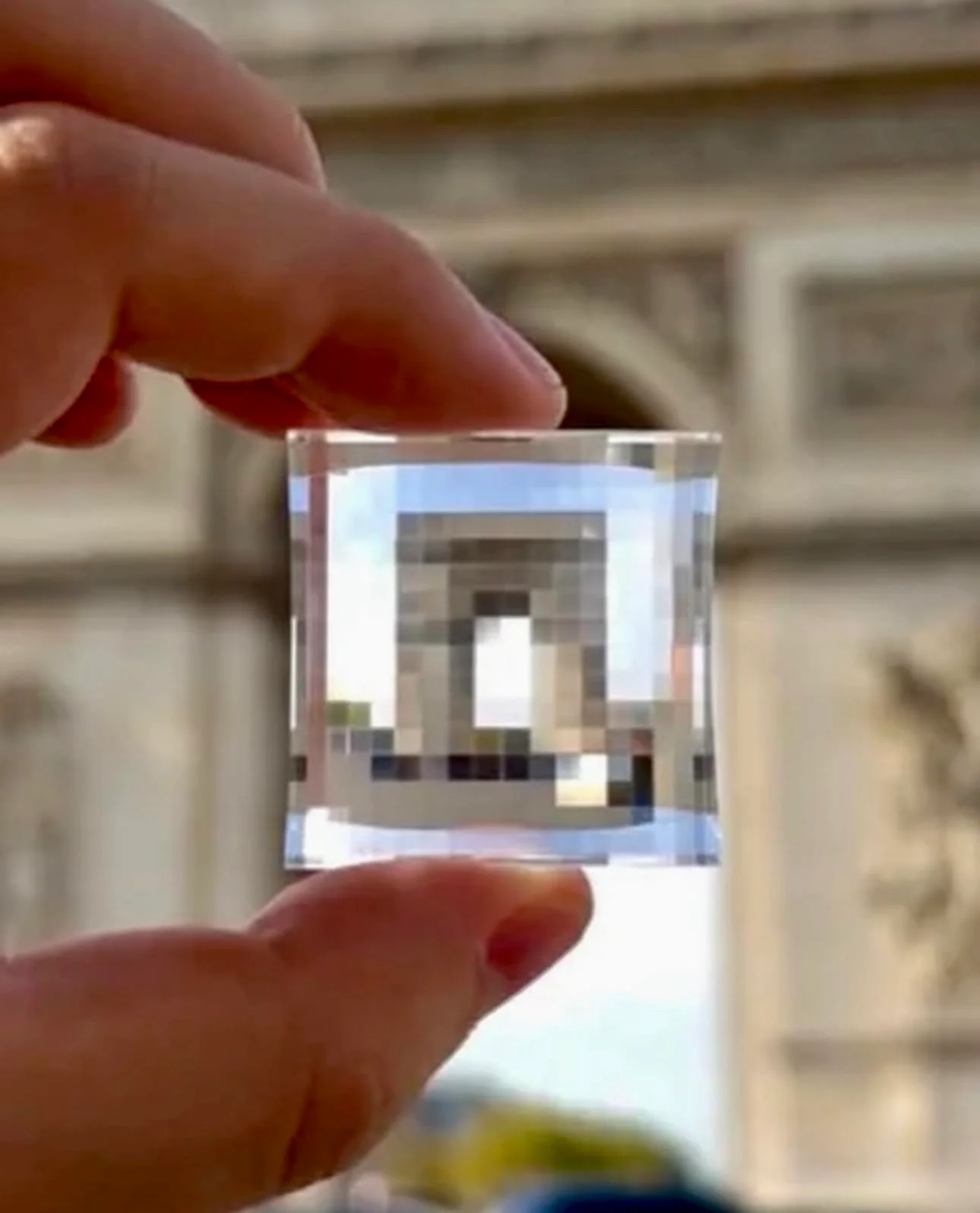

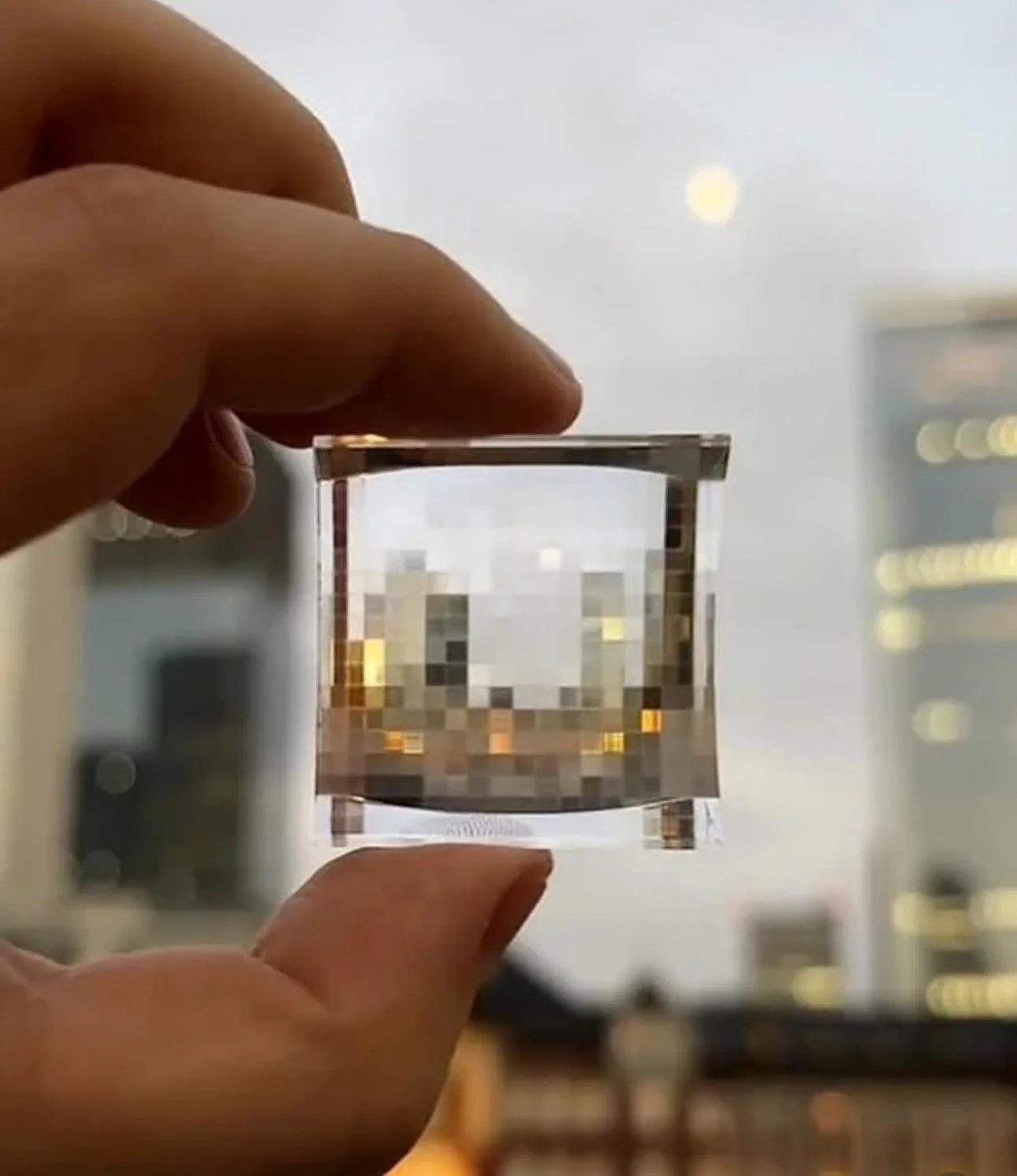

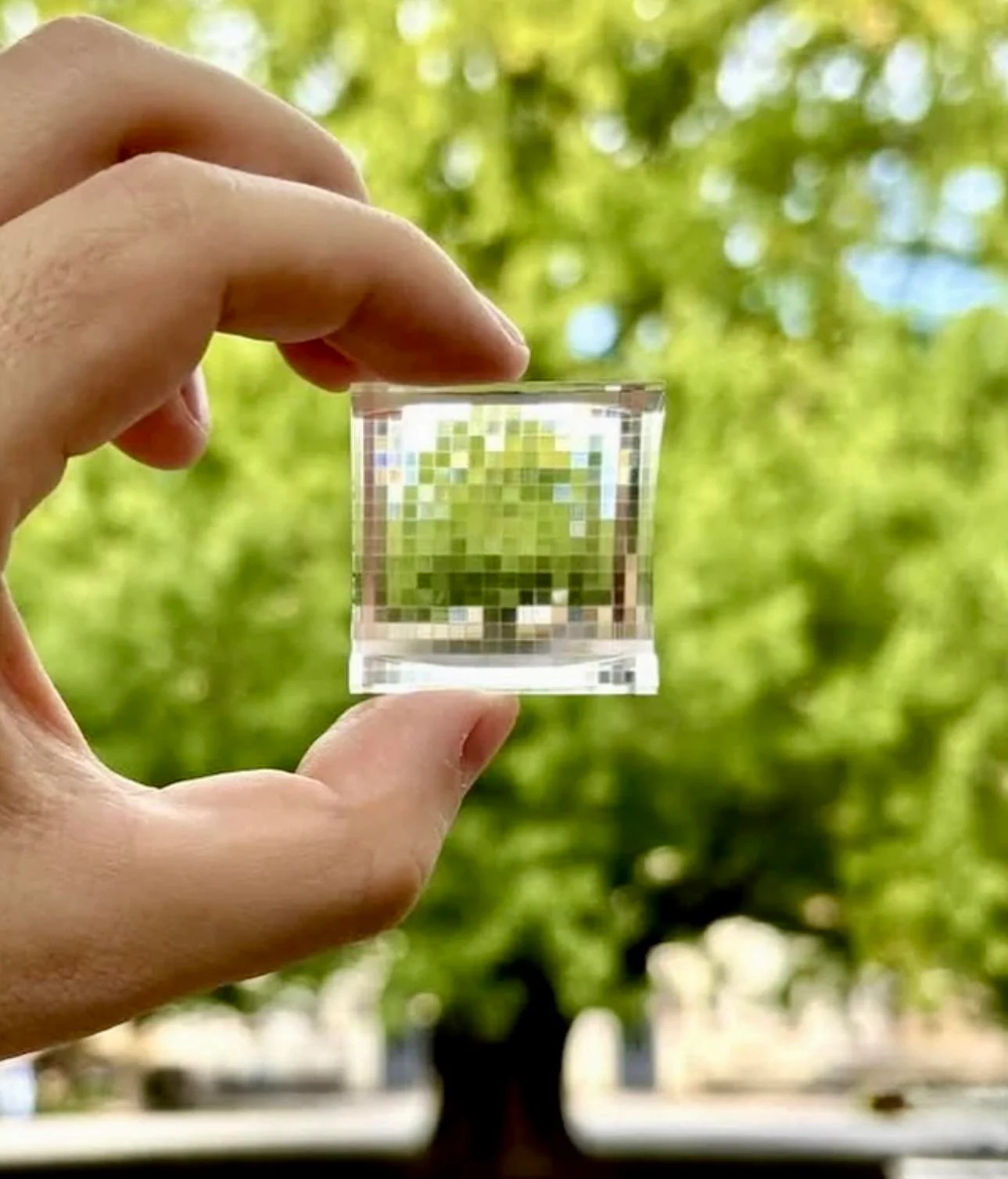

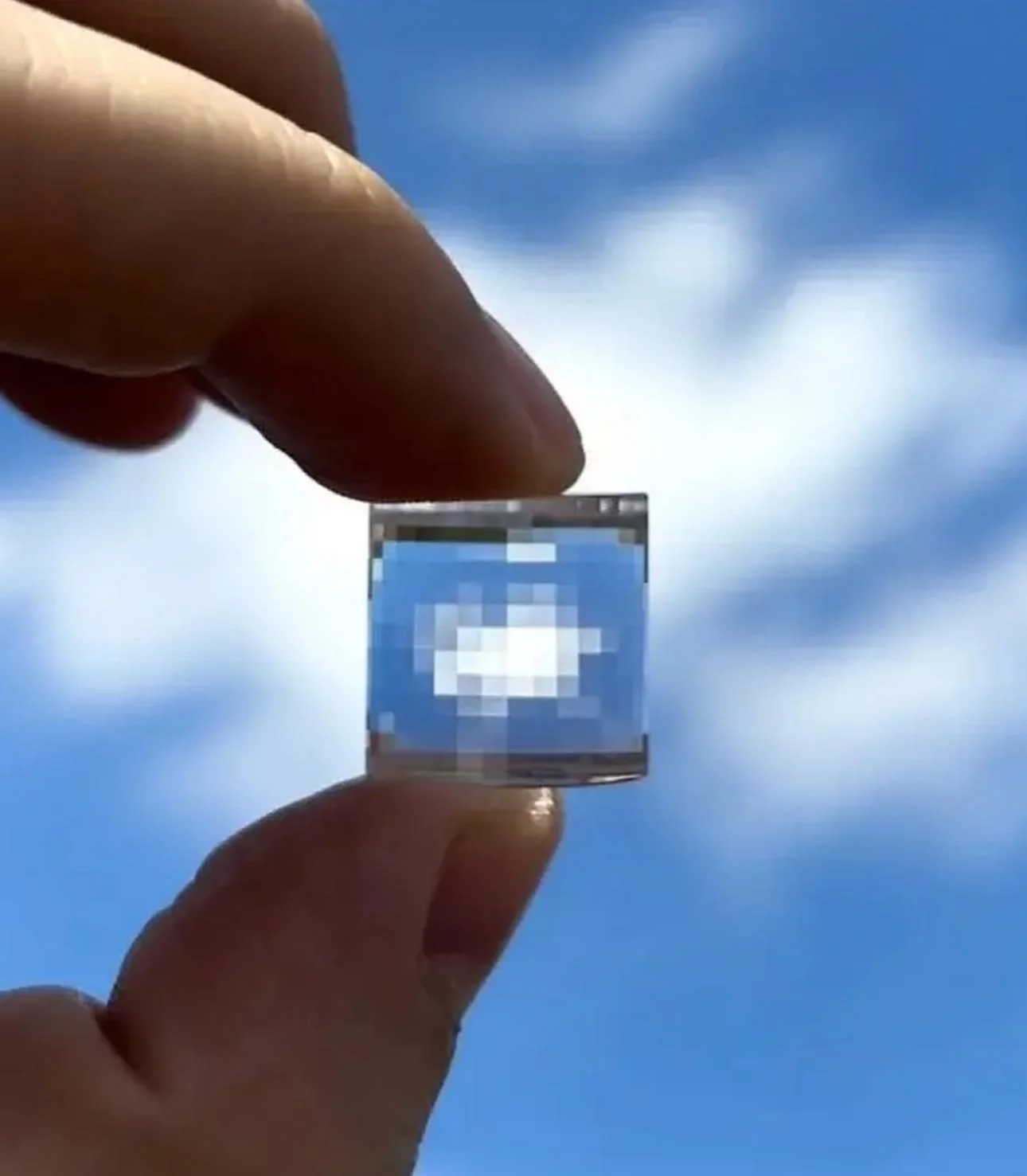

In an era where technology constantly strives for higher resolution and clearer imagery, Japanese designer Kentaro Okawara has taken a refreshingly contrarian approach with his creation: the “Reduced Reality Cube.” This small crystal device deliberately does the opposite of what most modern technology aims to achieve—it lowers the resolution of whatever you view through it, transforming our high-definition world into a pixelated landscape reminiscent of early digital imagery.

The Reduced Reality Cube is a transparent crystal prism approximately two inches in diameter. Made from optically clear resin with precisely crafted internal structures, the cube contains a carefully designed arrangement of microscopic lenses and prisms. When a user peers through the cube at any object or scene, these internal structures work together to “downgrade” the visual information, breaking continuous tones and shapes into distinct blocks of color—effectively pixelating reality.

Okawara designed the cube as both an artistic statement and a functional object that encourages a different way of seeing. In his artist’s statement, he explains: “In a world obsessed with higher resolution and perfect clarity, I wanted to create something that deliberately reduces information, forcing us to see our surroundings in a more abstract, simplified way. Sometimes less visual information can lead to more meaningful observation.”

What makes the Reduced Reality Cube particularly impressive is the technical precision required for its creation. Unlike digital pixelation, which is achieved through software algorithms, Okawara’s cube creates this effect purely through physical optics. The interior of the clear cube contains a complex three-dimensional grid of microscopic lenses, each capturing light and redirecting it to create the distinctive blockiness associated with low-resolution digital images.

The manufacturing process combines traditional crystal crafting techniques with modern optical engineering. Each cube is cast in clear resin before undergoing a precision grinding and polishing process. The interior optical elements are created using micro-etching techniques borrowed from semiconductor manufacturing, allowing for structures that manipulate light at nearly microscopic scales.

Different versions of the cube offer varying “resolution levels,” with some reducing scenes to just a few dozen colored blocks, while others create a more subtle effect with hundreds of pixels. Users can rotate the cube to change the orientation of the pixelation pattern or adjust the distance between the cube and their eye to modify the intensity of the effect.

The Reduced Reality Cube operates at the intersection of art, design, and philosophy. By deliberately reducing visual information rather than enhancing it, Okawara challenges our cultural obsession with ever-increasing clarity and detail. The cube asks users to consider what information is truly essential for understanding and appreciating what we see.

Art critics have noted how the cube transforms ordinary scenes into compositions reminiscent of abstract art or early digital aesthetics. A landscape viewed through the cube becomes a study in color relationships and simplified forms. A human face becomes a collection of colored blocks that somehow still retains its emotional essence, raising questions about how we recognize and interpret facial expressions.

Professor Yuri Tanaka of Tokyo University of the Arts describes the cube as “a physical manifestation of aesthetic reduction—a tool that strips away detail to reveal the essential structure of visual information. It’s particularly interesting how the human brain still manages to interpret and make sense of these reduced images, showing the remarkable adaptability of our visual processing systems.”

Beyond its artistic merit, the Reduced Reality Cube has found practical applications in various fields. Graphic designers and digital artists use it to gain new perspectives on their work, helping them consider how their designs might function at lower resolutions or when viewed from a distance. Architects have employed the cube to study how buildings might be perceived in different conditions or to evaluate the essential visual elements of their designs.

In educational settings, the cube has proven valuable for teaching concepts related to visual perception, digital imaging, and information theory. Students can directly experience how reducing visual information affects comprehension and recognition, making abstract concepts tangible.

Users report surprisingly emotional reactions to viewing familiar scenes through the cube. Many describe a sense of nostalgia, as the pixelated view reminds them of early video games or the first digital photographs. Others note how the cube helps them appreciate color relationships and compositional elements they might otherwise overlook in the detailed reality of normal vision.

Since its introduction at Tokyo Design Week, the Reduced Reality Cube has gained international attention, appearing in exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Design Museum in London, and numerous galleries across Asia and Europe. Its unique concept resonates with audiences tired of the relentless pursuit of higher definition in consumer electronics.

The commercial version of the cube, which Okawara produces in limited quantities through his design studio, regularly sells out despite its premium price point. Each cube comes in a minimalist package with a small stand and cleaning cloth, emphasizing its status as both a functional tool and a collectible art object.

The cube has inspired a wave of similar projects by other designers and artists, exploring different ways to deliberately “downgrade” or transform visual information. This growing movement represents a countertrend to the mainstream technology industry’s focus on ever-increasing resolution and clarity.

Building on the success of the original Reduced Reality Cube, Okawara is currently developing new variations that explore different types of visual transformation. One prototype applies color shifts rather than resolution reduction, transforming scenes into duotone or false-color representations. Another introduces temporal effects, creating subtle motion artifacts similar to those seen in early video formats.

Okawara is also collaborating with neuroscientists to study how the brain processes and interprets the reduced visual information provided by the cube. This research may offer insights into human visual perception and how we extract meaning from limited visual data—potentially informing fields ranging from artificial intelligence to accessibility design for people with visual impairments.