In the tapestry of cartographic history, few artifacts capture the imagination quite like the world map created by Henricus Martellus Germanus in 1487. This extraordinary document represents far more than a mere geographical representation; it is a window into the intellectual landscape of the late 15th century, a time of unprecedented exploration and expanding worldviews.

Henricus Martellus, a German cartographer working in Florence, Italy, stood at the crossroads of medieval knowledge and Renaissance discovery. His map was a testament to the rapidly changing understanding of global geography during an era of maritime exploration. At a time when most Europeans’ conception of the world was limited and often mythical, Martellus was compiling geographical information from the most recent maritime expeditions and scholarly research.

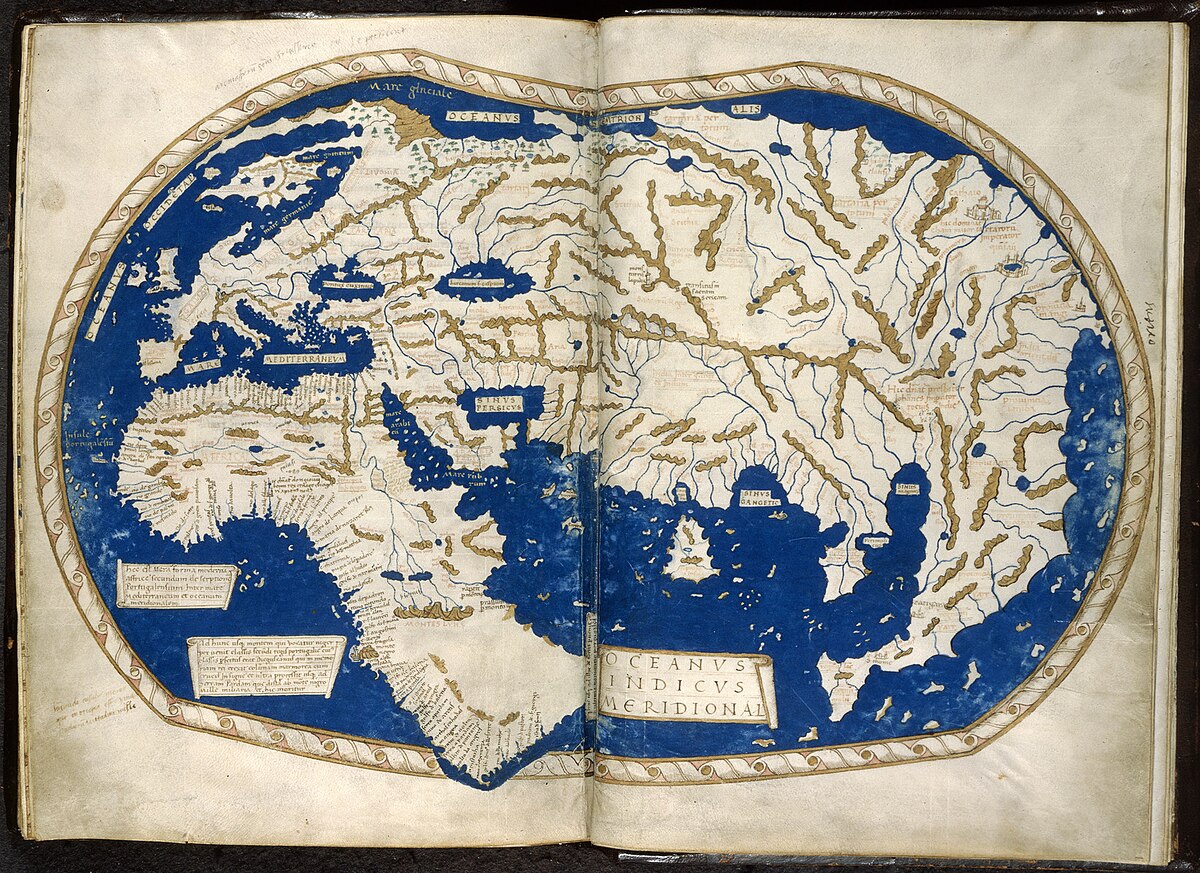

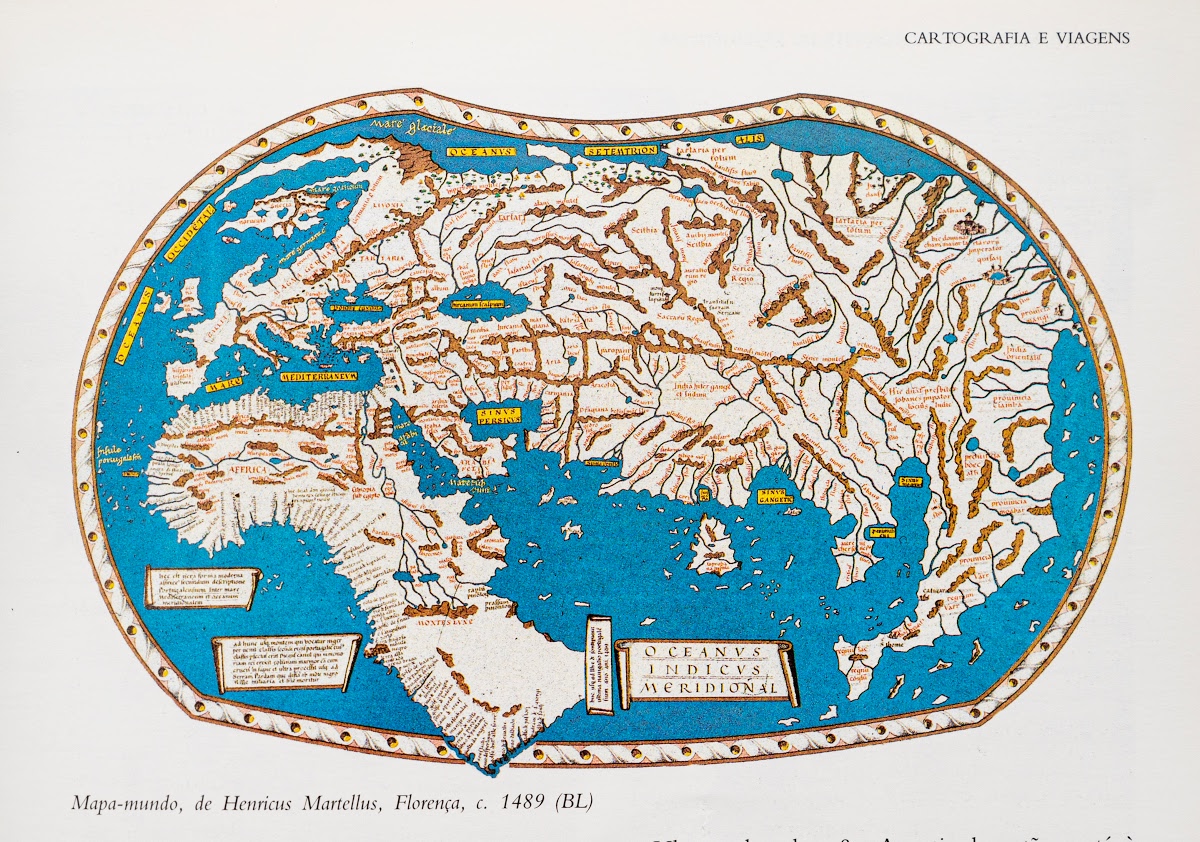

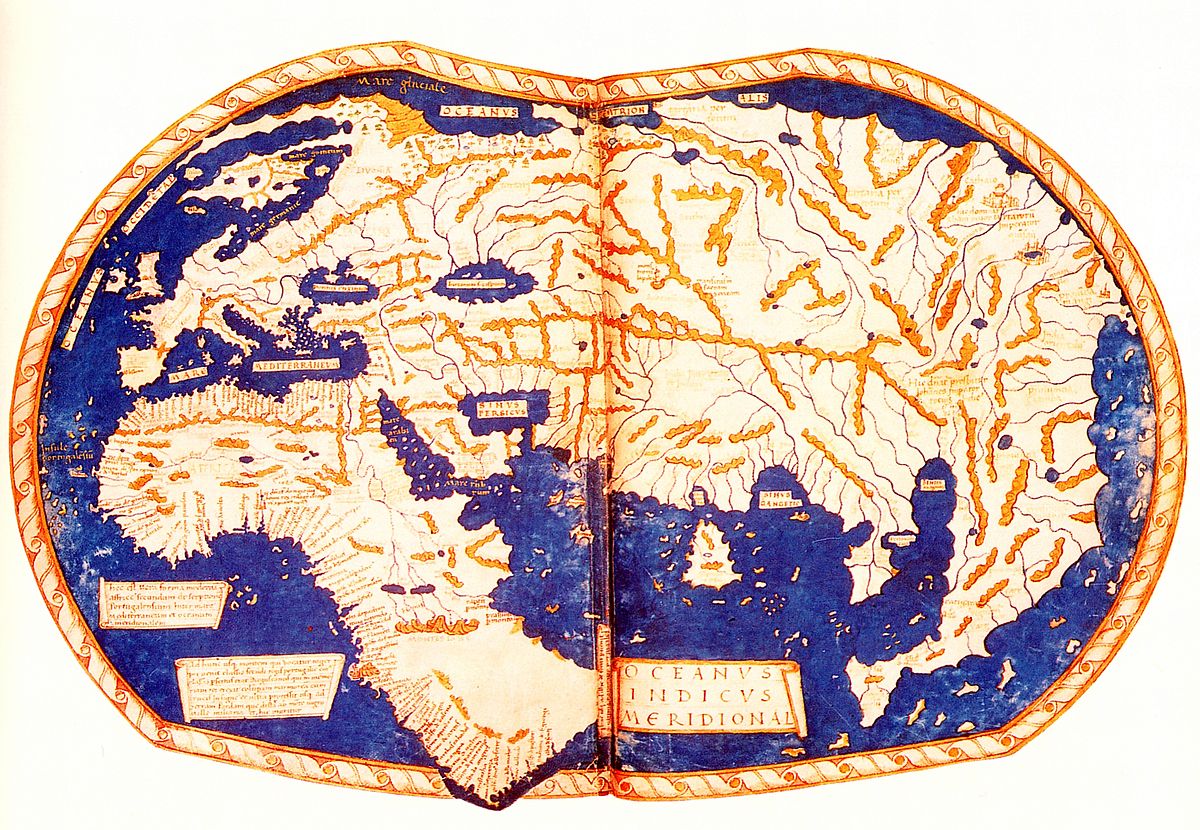

The map itself is a large, hand-drawn masterpiece on vellum, measuring approximately 2 feet by 4 feet. What makes it truly remarkable is its unprecedented level of detail and accuracy for its time. Unlike many contemporary maps filled with fantastical creatures and uncertain territories, Martellus’s work was grounded in empirical observations and emerging geographical knowledge.

Martellus’s map showcased several groundbreaking geographical insights. It provided one of the most detailed representations of Africa prior to Portuguese exploration, including intricate coastlines and interior details that were revolutionary for its era. The map incorporated information from Portuguese explorers who had been circumnavigating the African continent, gradually revealing its true shape and extent.

In the Americas, while the continents were not yet fully understood, the map hints at the emerging awareness of lands beyond the known European world. The representations of coastlines and landmasses reflect the transitional understanding of global geography during this critical period of exploration.

The map was created using the sophisticated techniques of Renaissance cartography. Martellus employed advanced methods of projection and utilized the latest geographical information available. He was heavily influenced by the works of Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, a mathematician who had corresponded with Christopher Columbus and proposed maritime routes across the Atlantic.

Interestingly, this map is believed to have been a significant inspiration for Christopher Columbus. Some historians suggest that Columbus might have studied this very map before his voyages, using it to inform his understanding of potential routes to Asia. The map’s detailed representations of known lands and speculative territories would have been invaluable to an explorer contemplating transoceanic journeys.

What makes the Martellus map truly fascinating is its position as a bridge between medieval misconceptions and emerging modern geographical knowledge. It represents a moment of transformation, where mythical interpretations were gradually being replaced by empirical observations and systematic exploration.

The map combines elements of medieval cartographic traditions—such as elaborate decorative elements and symbolic representations—with increasingly accurate geographical information. This blend makes it not just a navigational tool, but a complex cultural artifact that reflects the intellectual transitions of its time.

Today, the map is preserved in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, where it continues to fascinate historians, cartographers, and scholars. Modern digital technologies have allowed for even more detailed studies of its intricate features, revealing layers of geographical understanding that were revolutionary for the late 15th century.

Henricus Martellus Germanus’s 1487 world map is more than a historical document. It is a testament to human curiosity, the spirit of exploration, and the constant human desire to understand and map our world. It represents a moment when the boundaries of known geography were expanding, and the concept of a global world was beginning to take shape.

In this single artifact, we can trace the intellectual journey from medieval insularity to Renaissance global awareness—a transformation as profound and expansive as the very world being mapped.