In the halls of Madrid’s Prado Museum hangs a painting that has captivated, confused, and challenged viewers for nearly four centuries. Diego Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” (1656) stands as one of Western art’s most analyzed works—a complex composition that boldly breaks the fourth wall and invites endless interpretation. This ambitious canvas doesn’t merely depict a scene; it questions the very nature of representation, reality, and the relationship between artist, subject, and viewer.

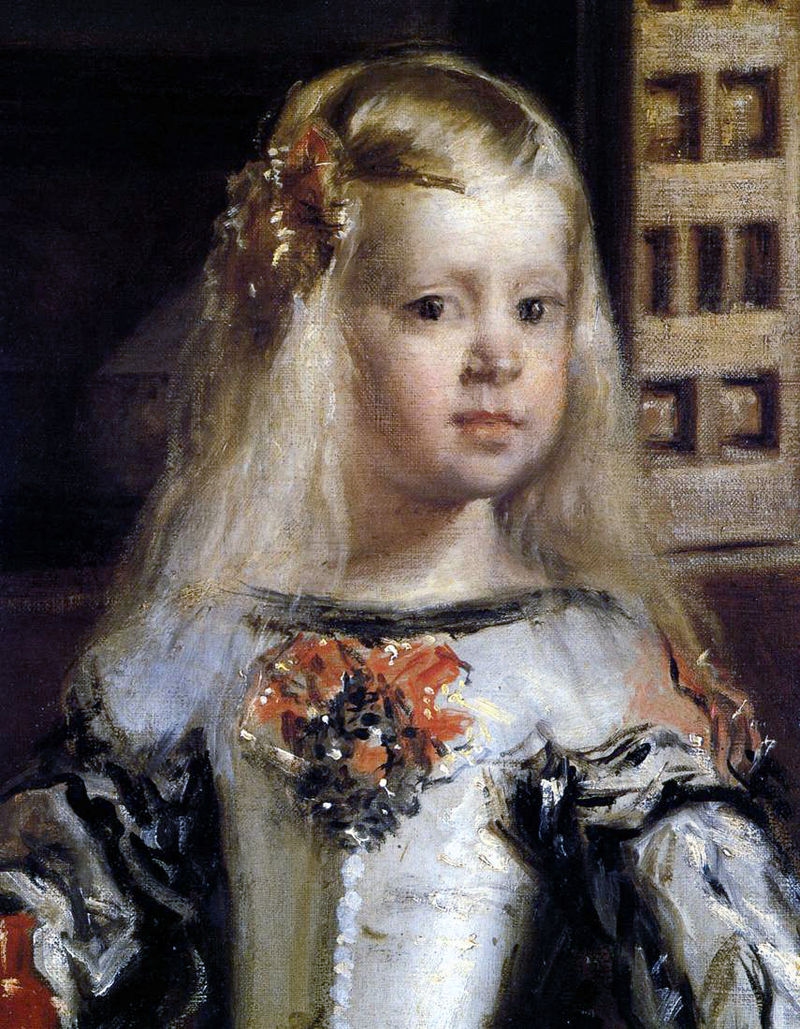

At first glance, “Las Meninas” (The Ladies-in-Waiting) appears to be a snapshot of daily life in the Spanish royal court. At the painting’s center stands the young Infanta Margaret Theresa, surrounded by her entourage of maids of honor, bodyguards, dwarfs, and a large dog. But this is where the straightforward reading ends and the mysteries begin.

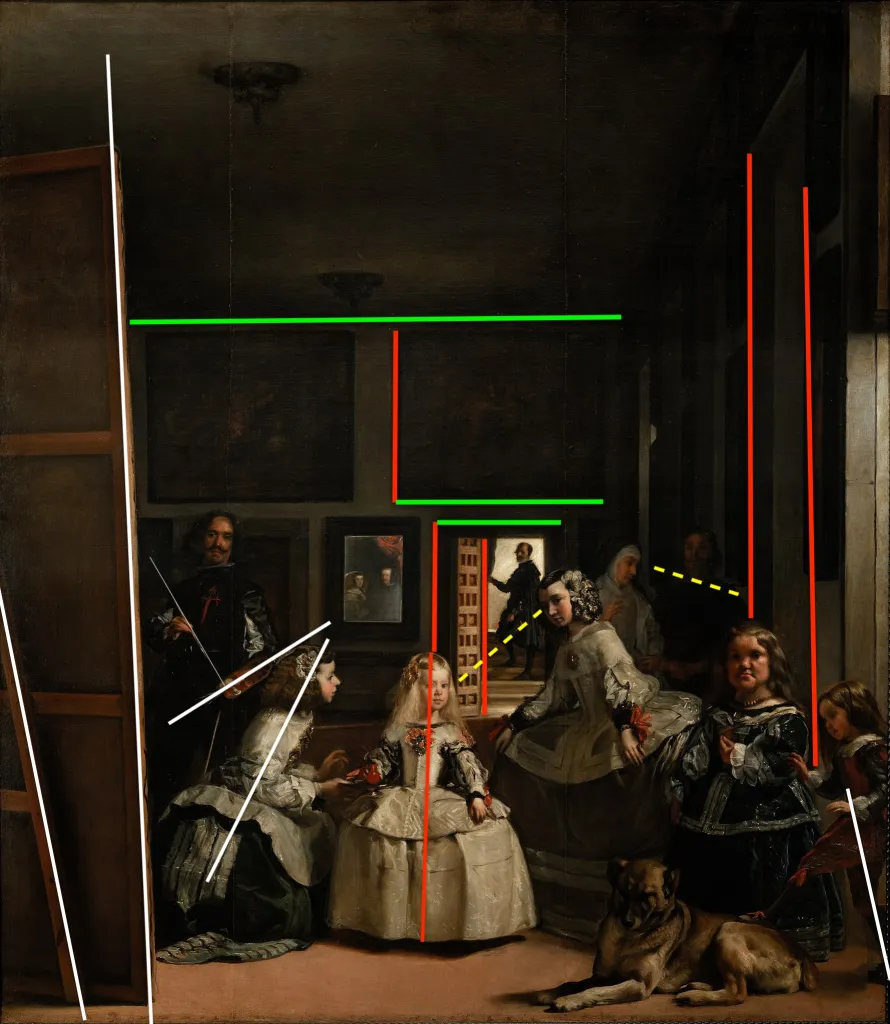

Velázquez himself appears prominently on the left side, standing before an enormous canvas, palette and brush in hand. His direct gaze meets the viewer’s eyes with a look of momentary interruption. Behind the central group, a mirror on the back wall reflects the barely discernible images of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana of Austria. Meanwhile, in the doorway at the rear stands the queen’s chamberlain, paused mid-departure or arrival.

What makes “Las Meninas” revolutionary is its unprecedented disruption of traditional pictorial space. Velázquez’s self-inclusion as the artist at work represents one of art history’s earliest and most sophisticated examples of breaking the fourth wall. Unlike previous self-portraits, Velázquez doesn’t merely insert himself as an observer but as an active participant in a complex spatial and conceptual puzzle.

His direct gaze confronts viewers with an unsettling question: What exactly are we witnessing? Are we standing where the king and queen would be, becoming unwitting participants in the scene? Is Velázquez painting us, or are we interrupting him as he paints the royal couple? The painting’s perspective deliberately creates this ambiguity.

The small mirror on the back wall provides another layer of complexity. Reflecting the hazy figures of the royal couple, it throws conventional understanding of the painting’s spatial arrangement into disarray. Are the king and queen physically present in the room, standing where we, the viewers, would be? Or is Velázquez painting their portrait, using the mirror to check his work?

Art historians have debated these questions for centuries. The mirror serves as both a technical device and a philosophical statement about representation and reality. It forces us to consider what lies beyond the frame—what Velázquez sees that we cannot.

Perhaps most intriguing is how Velázquez orchestrates the painting’s network of gazes. Almost every figure looks in a different direction, creating a web of sightlines that refuses to resolve into a single narrative. The Infanta looks toward the viewer (or her parents), the maid on the right kneels in attentive service, Velázquez studies something beyond the frame, and the man in the doorway pauses to observe the scene.

These varied gazes create a dynamic tension that keeps the viewer’s eye moving throughout the composition, never settling on a definitive interpretation. This deliberate destabilization of perspective was centuries ahead of its time, anticipating techniques that wouldn’t become mainstream until modern art in the 20th century.

Beyond its technical innovations, “Las Meninas” offers profound commentary on art, reality, and social hierarchy. By prominently featuring himself—a court painter—alongside royalty, Velázquez subtly elevates the status of the artist in an era when painters were often considered mere craftsmen. His prominent signature on the painting and the Order of Santiago cross on his chest (possibly added later) further emphasize this assertion of artistic dignity.

The painting also serves as a meditation on representation itself. What appears to be a straightforward scene becomes, upon reflection, an exploration of how art constructs reality rather than simply reflecting it. In this, Velázquez anticipates postmodern concerns about simulation and representation by more than three centuries.

“Las Meninas” continues to inspire artists, philosophers, and viewers alike. Michel Foucault devoted the opening chapter of his seminal work “The Order of Things” to analyzing it. Pablo Picasso created 58 variations of the painting in 1957. Contemporary artists still reference its groundbreaking meta-techniques when exploring self-referentiality in art.

What makes “Las Meninas” endlessly fascinating is not just its technical brilliance or compositional complexity, but its refusal to yield a single, definitive interpretation. In creating a work that questions the very act of creation itself, Velázquez crafted not just a masterpiece of Spanish painting but a philosophical puzzle that continues to challenge our understanding of how we see, what we represent, and how art mediates between reality and perception.

In the centuries since its creation, Velázquez’s enigmatic masterwork has never stopped asking questions of its viewers—making it not just a painting of court life, but a painting about painting itself.